BY KELLAN BYARS

Multimedia Journalist

Frankenstein has been stitched together dozens of times on screen, but Guillermo del Toro’s newest rendition feels like the first time the monster truly opens his eyes. In most Frankenstein stories, the horror lies in the monster. Del Toro chose a different route, revealing the horror that lies in humanity.

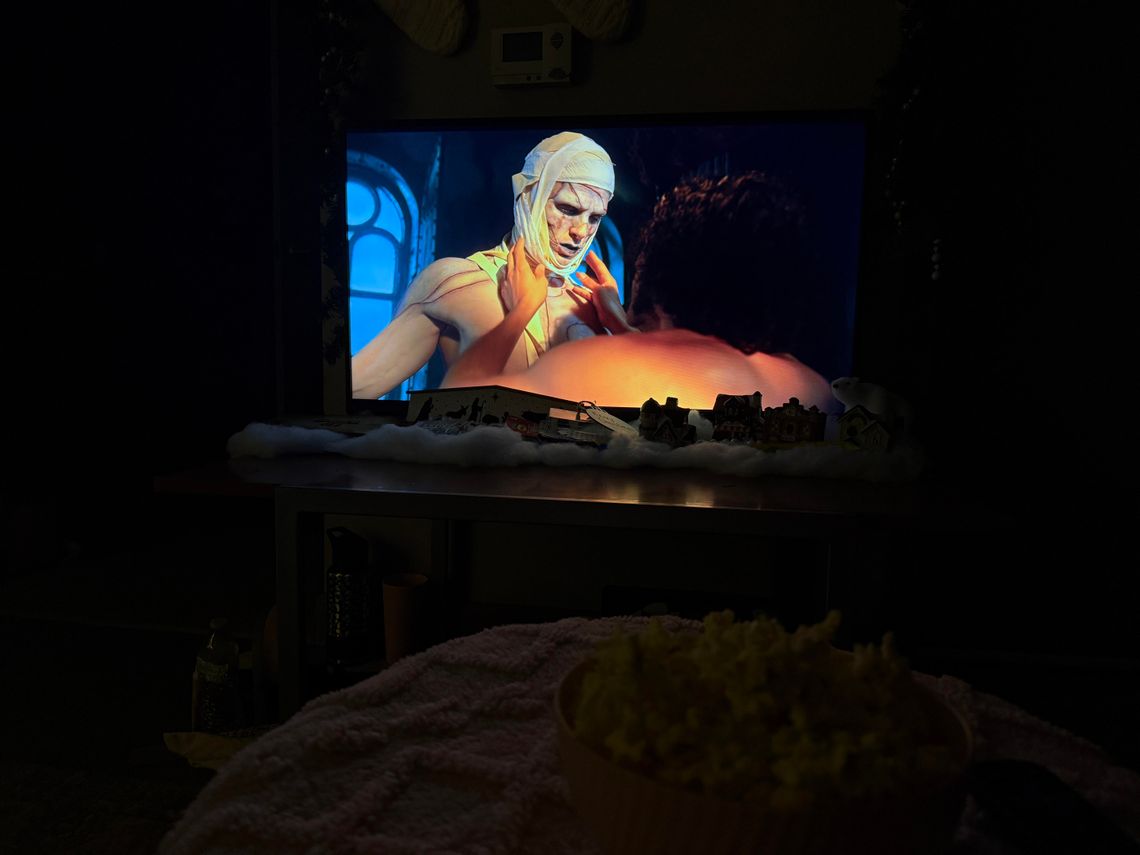

In del Toro’s “Frankenstein”, released on Nov. 7, 2025, he crafts a grotesquely beautiful adaptation of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel – one that reimagines the familiar tale as an emotionally layered story not only about the man behind the monster, but about the impossible weight of the life he creates and the humanity he refuses to recognize.

One of the most striking differences I found in this adaptation is del Toro’s focus on humanity as the true source of horror. Previous versions lean heavily on the idea of the physical monstrosity of the creature.

Del Toro totally rewrites that idea. His creature was played in an almost curiously vulnerable way by Jacob Elordi. The creature is less of a monster and more of a mirror revealing the cracks and cruelty in his creator and the world that rejects him.

The film refuses to present him just as a villain. Instead, he becomes a tragic byproduct of Victor Frankenstein’s ambition and emotional emptiness.

Victor, through del Toro’s eyes, is not just a mad scientist but a man driven by grief and an addiction to controlling every aspect of life and, eventually, death. Del Toro reshapes him into a character who genuinely believes he can outsmart death but overlooks the moral cost of bringing life into the world without considering how to care for it.

The dynamic between Victor and the creature becomes the emotional backbone of the film, one of a creator unable to confront or care for his mistakes and a creation desperate to understand his existence.

What makes this adaptation stand out to me is del Toro’s ability to balance the grotesque and beautiful. His visual world is richly textured, filled with the dark romanticism that defines his filmmaking. I found myself entranced in a sense of decaying elegance that creates a storybook-gothic atmosphere.

Del Toro’s Frankenstein world is not simply gloomy or depressing; it is alive, breathing with a sense of emptiness and longing for companionship.

The creature’s design reflects this perfectly. He is towering, scarred and almost statuesque, yet strangely graceful, embodying both horror and childlike innocence in an odd balance.

I enjoyed how del Toro’s direction allowed each character to be more than their traditional archetype. Elizabeth Lavenza is not merely a damsel in distress; she is intelligent and someone who sees Victor’s unraveling long before he admits it himself.

The cast truly embodied the struggle between morality and the human tendency of self-preservation and comfort at the cost of another’s life.

The creature’s search for belonging was incredibly moving. His encounters with society—whether with fearful villagers or with souls who briefly show him kindness—are shown in a quietly powerful way.

Del Toro lingers on these moments, allowing the audience to experience the creature’s inner conflict almost as if living through him. Instead of framing him as an uncontrollable force, the film treats him as a tragic victim of a world unable to accept difference.

This change alone sets del Toro’s adaptation apart from decades of versions that reduced the creature to an unthinking, unfeeling threat.

The film does carry much of del Toro’s traditional style: elaborate production design, symbolic use of color and emotional storytelling rooted in the macabre. Yet it avoids becoming predictable.

While some may expect his signature monsters and fairy-tale darkness, they will find something far more intimate. A story where the greatest wounds are not inflicted by supernatural forces but by human neglect and fear.

In many ways, this “Frankenstein” feels like the thematic sibling of another of del Toro’s works, “The Shape of Water”: a narrative about beings who are misunderstood, feared and ultimately shaped by the failures of the humans around them.

What truly elevates the film is its moral clarity. Del Toro does not shy away from condemning Victor’s choices, nor does he excuse the creature’s violence. Instead, he presents both as inevitable outcomes of emotional abandonment.

Giving humanity to the creature was almost heartbreaking to experience. I could feel the emotions of both Victor and his grief and the longing the creature felt to be understood. I felt that del Toro was trying to make me question what separated the man and monster. Through his direction he translated that the creature’s creation did not make him a monster. It was the cruelty he was shown.

In the end, “Frankenstein” becomes more than a traditional horror story. It becomes a meditation on grief, ambition and the revolting nature of humanity.

Del Toro’s adaptation proves that the story still has something urgent to say, especially when placed in the hands of a filmmaker who understands that monsters are most compelling when they reveal uncomfortable truths about themselves.

.png)

Comment

Comments